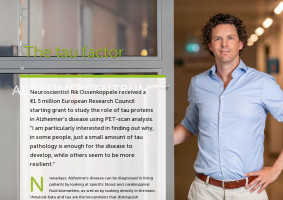

Neuroscientist Rik Ossenkoppele received a €1.5 million European Research Council starting grant to study the role of tau proteins in Alzheimer’s disease using PET-scan analysis. “I am particularly interested in finding out why, in some people, just a small amount of tau pathology is enough for the disease to develop, while others seem to be more resilient.”

Nowadays, Alzheimer’s disease can be diagnosed in living patients by looking at specific blood and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, as well as by looking directly in the brain. “Amyloid-beta and tau are the two proteins that distinguish Alzheimer’s from many other types of dementia,” explains Associate Professor, Rik Ossenkoppele. “Amyloid-beta can already be found in the brains of patients 20 years before the disease’s clinical symptoms manifest. Tau, on the other hand, aggregates in the neurons in the brain. If you aim to detect tau, you need tracers that can not only pass the blood-brain barrier but that also have the ability to enter cells.”

Valuable diagnosis

There are some tracers on the market today that can label the pathological aggregates of tau proteins and thus make tau visible on a PET scan. “Interestingly, many of the tracers failed as pharmaceutical agents and were given a second life in diagnostics,” says Ossenkoppele. “Companies probably can’t make as much money from diagnostics as from therapeutics, but an accurate diagnosis is very valuable too. Even in the absence of an effective treatment, it is worth knowing, both for the patient and for their loved ones, what the prognosis of dementia will be. Also, for research, tau-PET, with its link to clinical Alzheimer’s, is indispensable to advance our knowledge of this disease.”

What makes a person resistant to tau pathology?

Ossenkoppele and his colleagues have shown that tau pathology strongly correlates with cognitive symptoms. However, there is no one-on-one relationship between the degree of tau and Alzheimer’s severity. “In some people, it takes just a small amount of tau pathology to develop serious cognitive decline, while others are much more resilient.”

With his recently awarded European Research Council grant, Ossenkoppele will try to find out where the difference between these resilient and non-resilient individuals lies. “We will take three approaches,” he explains. “First, we will relate brain networks to the tau burden in the brains of people affected by Alzheimer’s. By using a functional MRI scan, we can see which regions of the brain are active together during specific tasks. I hypothesize that a brain with stronger networks is able to resist the aggregation of tau for a longer time, thereby decelerating the rate of cognitive decline.”

Biomarkers and genetics

In a second approach, Ossenkoppele and his colleagues will try to identify novel biomarkers, other than amyloid-beta or tau, that may be altered in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid of non-resilient patients as opposed to more resilient individuals. In a third and last approach, Ossenkoppele will look at the genetics of Alzheimer’s patients. “As far as I know, this will be the first-ever genome-wide association study on resilience against tau pathology in people with Alzheimer’s. Hopefully, this will lead to identifying pathophysiological mechanisms that tell us more about the onset of the disease. It might even provide new leads to potential treatments.”

Curing Alzheimer’s

The therapies for patients with Alzheimer’s disease that are on the market today are controversial. “Aducanumab, a drug that the US Food and Drug Administration recently approved, significantly clears amyloid-beta in the brain, but whether that results in a clear clinical benefit is yet to be determined,” says Ossenkoppele. “In a successful phase-II trial with a comparable anti-amyloid-beta drug, Donanemab, the amount of tau on a PET scan was used to include participants in the trial. This new approach has shown promising results, especially in people with just a small amount of tau pathology – suggesting that we need to intervene as early as possible. This gives us extra motivation to intensify our research on tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease.”

Photograhpy: Marieke de Lorijn