Read More

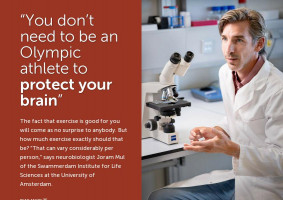

“It’s always a surprising eye-opener when I ask my students how much they think a mouse or rat runs during the night, the time when they are active,” says assistant professor of Neurobiology Joram Mul. “We provide our lab animals with an enriched environment, such as a hiding place and ‘toys’, in their cage, in addition to food and water. If we add a vertical running wheel, male mice can run six to seven kilometers per night; female mice sometimes even double that. With horizontal wheels, the distances are even greater. And it’s all on a voluntary basis. Wheel running clearly has some rewarding and self-reinforcing properties.”

Movement pays off

The effects of all that running are clearly visible in the animals’ brain, Mul says. “For example, the hippocampus and the nucleus accumbens are regions in the brain that play a role in mood and cognition, and which are known to improve with exercise. But we also see changes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the biological clock of the brain. We can observe this in the thin slices we take from the rodent brain. There we find, among other things, altered levels of the protein ∆FosB, which is produced upon the repeated activation of neurons. Also, when it comes to the animals’ physiology, we see an improvement in sugar metabolism, a reduction in fat reserves, as well as other aspects of a healthier metabolism.”

Biological clock

For the past three years, Mul’s research group has been working to demonstrate the positive effects of physical activity observed in laboratory animals and in humans as well. “In broad terms, of course, it is known that a certain amount of physical activity is beneficial to our health. Exercise during the day also strengthens a person’s circadian rhythm, and this, in turn, is associated with a reduced occurrence of depression or obesity. But we want to have a better understanding of how that works. And what is the exact amount of exercise necessary for individuals to benefit from these effects?”

Preventing relapse

To investigate that, Mul is participating in the StayFine study, funded by the University of Amsterdam’s Centre for Urban Mental Health. The study uses app technology to investigate how to keep healthy young people, who have a history of depression or anxiety disorder, from relapsing. “Up to 60% of those adolescents experience a relapse sooner or later. Using simple ‘wearables’, similar to the smartwatches that can record your daily movement and heart rate, we investigate the role of physical activity during this process, and test whether it can help prevent a relapse into depression or anxiety. We will follow the participants for three years, with several two-week periods during which they wear the instrument. Inclusion for that study is now in full swing.”

It doesn’t hurt to…

Even though the positive effects of exercise seem so obvious, Mul believes it is still not a good idea to get everyone to be as active as possible. “It’s too easy to say: ‘It doesn’t hurt to…’, because too much exercise can actually hurt. For example, sports injuries can result from bad equipment or technique, or from doing exercise at too high an intensity or frequency. In very extreme cases, people, usually top athletes, can even show withdrawal symptoms when they are forced to stop abruptly with exercise. It’s mainly about ‘the best of your ability’, as studies with large human cohorts demonstrate that, on average, roughly one-and-a-half hours of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week can lower the risk of developing depression. But I want to know how much exercise is necessary for each individual person for their brain to be protected, and then also: How do you get people with a full agenda, like students, to exercise more often?”

Indirect evidence

Apart from those highly practical questions, Mul also hopes to gain more insight into the fundamental biology of exercise and its effects on the brain. “The possibilities for collecting biological information from the brains of humans are still limited. At the Netherlands Brain Bank (a department of the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience), for example, there aren’t many donors known to have exercised a lot during their lives and then died in an acute manner, so it’s difficult to study long-lasting adaptations in the human brain. In mice, however, we can study exercise-induced adaptations in their brain in great detail, after a life of more, or less, physical activity. So, for the time being, we will have to work with animal data. We also use existing, large databases, such as the UK Biobank, which contains information from more than a hundred thousand Britons who have also worn a wearable to monitor their physical activity.”

Centralize the staircase

Despite his search for solid scientific evidence on the individual amount of exercise that is necessary to protect the brain, Mul already sees plenty of evidence for wanting to improve people’s current physical activity patterns. “Look around you and see how society increasingly discourages physical activity. You see people standing passively on escalators or taking the elevator instead of the stairs, and an increasing number of youngsters ride e-bikes. We really can and should do better. In architecture, for example, we should place stairways in the centre of a building rather than elevators. That is just one simple way to get our daily dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, as recommended by the WHO. And really, you don’t have to become an Olympic athlete; just 90 minutes of intensive exercise per week can already have a positive effect on your brain.”

Photography: DigiDaan